My Singing Story

Why I do what I do, and “somatic semantics”

Darren Clarke

2/15/20246 min read

Whilst building my course of “Ting Song” - Qi Gong for singers and vocal professionals” there are days where, inevitably, it feels like it will be amazing and helpful for everyone; at other times it can lead me down a self-doubting rabbit hole. In the latter moments I ask myself why I began thinking of it in the first place.

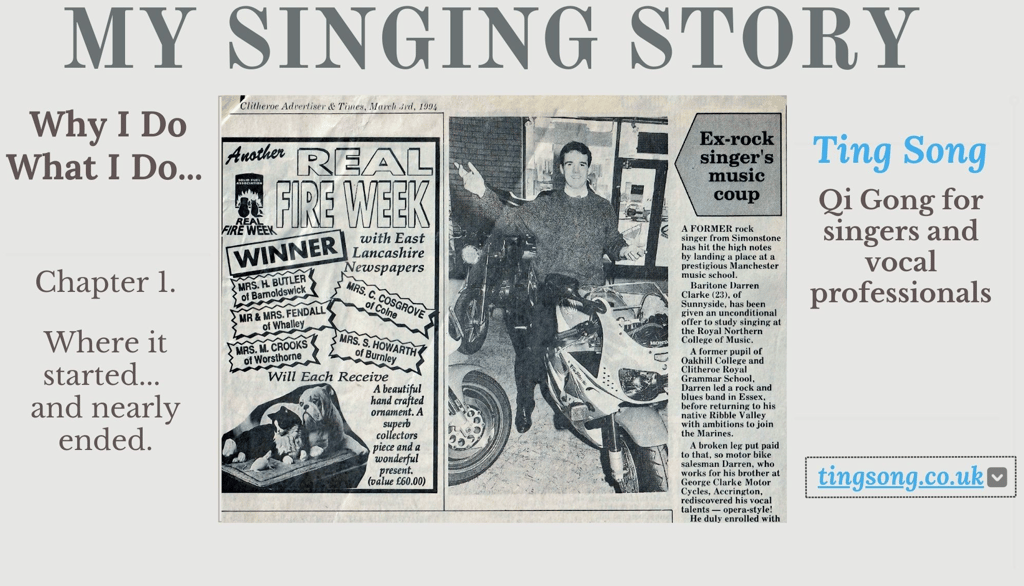

I thought I’d start with a relatively shortened version of the course of events: I remember being overwhelmed with joy at opening the letter from the Royal Northern College of Music telling me I had a place on the undergraduate course. It was the happiest moment of my life at that point as a twenty-three year old aspiring singer! The competition for a place had been immense that year (so I was later told) and yet some sort of potential had been seen in my high baritone with a promising instinct for acting. Even though I’d led a number of lives already at such a tender age (if I was a cat I probably would have lost a few) most had led to disappointment or disaster one way or another and I hadn’t found my calling - up to this point.

I was relatively experienced with certain aspects of the “real world” and yet I was still immature in other ways. I’d learned from my adoption to protect my insecurities by being fairly affable or gregarious and sometimes this led me to sometimes burning the candle at both ends. I did, however, have a strong work ethic and no matter what had happened the night before I would usually be practising first thing in the morning and attending classes. I was also (perhaps naively) loyal and very trusting of my allotted singing teacher.

I hadn’t studied music formally, only obtaining Grade V theory and VIII singing just before my RNCM audition, so it was quite a culture shock from selling motorbikes in Accrington or training to be a marine. However, I met some wonderful people at the Manchester Conservatory, including several staff and co-students who were very supportive, some of whom are lifelong friends.

Sadly the joy of learning my craft and the ability to sing with it diminished after four years which resulted in my neck and upper torso being so physically tense that I could barely talk and turn my head at the same time, let alone sing (which I accomplished by positioning my head to one side and at an angle in order to squeeze out a sound). Everything was essentially locked up when I tried to sing - my chest, ribs, diaphragm, jaw, tongue, neck, face, scalp, shoulders, abdomen, hips, legs. In all honesty, I don’t think there was any part of me where, with hindsight, the wrong kind of effort wasn’t being employed!

With an ever decreasing range of notes, dynamics and a very tight sound, there was no point during my training at the RNCM (or later with some other teachers and coaches) when the question was asked: “How does that feel for you?”. There were tutors who, because I couldn’t do what it was they were asking of me, simply stated that they had no idea why I was even there. “You’ll never be a professional singer! You haven’t got the voice.” Maybe they were right in their own way because if it meant singing like some of them, I’m glad that I couldn’t do it! For some, it was as though they believed that all singers came blessed with the appropriate physiological makeup and mental aptitude to become the sort of singer the teacher perceived themselves to be, or could have been...

Some outlandish and potentially dangerous ideas included pushing pianos with the diaphragm (they needed lessons in anatomy!) - one teacher even put his fist into my solar plexus and told me to push it out whilst singing. Pull the vocal cords back like a catapult, was another instruction. Raise the cheekbones. Keep it bright. Lift the palate. Turn the screw. The list of unfounded or unexplainable phrases go on:

One must place the voice here or there.

Sing in the mask.

Sing from the top of your head.

Sing from or on the diaphragm.

Support.

Cover the sound.

Project.

These are only some examples of the phrases that I heard that are, with hindsight in my opinion: misguided concepts that have been adapted for poor technical skill and others are a dilution of a result transmitted as a cause. A few of these phrases might possibly have some meaning to someone; but perhaps more accurately did mean something to someone at some time. They passed it on as a description of how their singing or a part of their singing felt to them. This in turn was passed on to another person or persons and, whether they felt it or not, the phrase continued to be used until it became an instruction. I call them “somatic semantics” (or the interpretation and attempted explanation of how something feels from one individual to another) that have been passed down from one generation of singers and teachers to another. Corrupted phrases indicating inaccurately transmitted information and “Chinese Whispers” which, unfortunately, for some people have become the creed of classical singing institutions.

I’m not saying that some of these somatic statements can’t or shouldn’t be “noticed” by an individual as part of self enquiry. However, in my opinion and experience, we should always be cautious about pursuing an effect and pay attention to how it affects our physical and mental state. So many times have I witnessed singing teachers that have certain nuggets of information, techniques or insights and dish them out to their students, in the hope that the student will just “get it”, somehow. Let’s say one of these teachers was instructing a breathing technique, for instance, and they simply presented it, showing how it's done. They might have demonstrated it and then proceeded to guide their students through the steps. By following their instructions and mimicking the process, the student presumably should reap the same benefits as the teacher. This approach of imparting technique purely through transmission without much room for questioning or allowing space for the student to embark on a unique experience doesn’t serve the majority of students. With this “monkey see, monkey do” intention, the individual student chases the effect and loses the ability to start from a different physical and mental experience to that of the teacher.

Sadly in some cases if the student doesn’t “get it” then they may be considered to be either not very good or even stupid. Alternatively they create the desired effect for years, ignoring any affect the technique (or multiple techniques) is having on them until one day they have a blip or crisis of technique, finding singing more and more difficult until they can no longer perform either through a breakdown of confidence, mental or physical wear and tear or both. Self-enquiry without some form of technique can be chaotic but a technique that pursues results without enquiry is nothing more than dogma.

I didn’t or couldn’t do what some instructors and coaches wanted me to do at college; I ended up with laryngitis trying to do what one teacher told me to do, the ENT consultant showed me my inflamed vocal folds and said how lucky I was that I didn’t have nodules. Even after recovery my voice became more and more restricted and decreased in range. I became a “bad fit” with the establishment as my voice became “too small for opera” (not my words). I strangely thought that to sing well shouldn’t be as much hard work as some of these people made it out to be. I took some refuge with a handful of the well respected but less influential tutors, some that had retired from professional singing careers that taught song classes. These few were the exception to the many and although they kept their opinions as to some of the teachers that have been mentioned fairly closely guarded, they exemplified that singing as well as one can doesn’t mean having to manipulate or push or squeeze or indeed - “work” that hard.

I suppose it boils down to what “hard work” or “working hard” sometimes actually entails? Passion, dedication, self discipline and commitment I certainly had and still have to this day. Otherwise I wouldn’t be writing about my pursuit of how I can release unnecessary tensions in my own breathing, singing and speaking and so do my best to help other singers or those that don’t fit “the mould”.

It’s possible that with so many people that sing professionally, semi- professionally and amateur alike that are or have been affected by the singing teaching profession are aware of the elephant in the room and are now willing to call these things out. It certainly appears that I’m definitely not alone in having experienced or discovered that some methods of teaching others to sing simply need to be discarded, or at the very least, the student (and the teacher) needs to be made aware that repeating a wrong thing will never make it the right thing to do.